Grandeur factory - specialising in the mesmerising

The Legacy of Cubism: Fragmenting Reality to Create New Perspectives

Brian Iselin

9/5/20244 min read

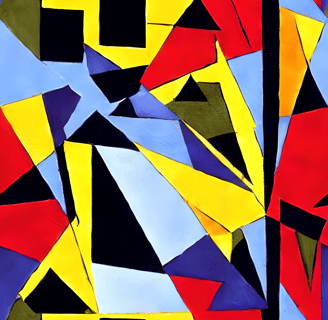

Cubism has always fascinated me for the way it messes with how we see the world. It’s like taking something familiar—an object, a person, a scene—and looking at it from every angle at once, smashing it apart, and putting the pieces back together in a totally new way. The result is something that’s both recognizable and completely foreign. And that’s what makes it so powerful, both in its original form and how it influences my own work today.

Breaking Things Apart to Find Something New

When I create a piece that’s influenced by cubism, I’m not aiming to represent things as they are. Instead, I’m interested in how breaking something down—whether it’s a face, a building, or even just a feeling—can reveal something new. There’s a sort of freedom in deconstructing reality. By taking something that’s normally solid and familiar and pulling it apart, you can start to see things in ways that aren’t immediately obvious.

In my artwork, this often happens organically. I’ll start with a basic shape or image, something concrete like a figure or an object, and then let it evolve on the canvas. As I break it down, the lines and shapes take on a life of their own. Maybe a face turns into a collection of geometric shapes, or a still life becomes a scattered mosaic of angles and colors. It’s like I’m taking something that feels rigid and pulling it apart to explore the space within it.

Seeing Multiple Perspectives at Once

One of the key elements of cubism is that it allows you to see multiple perspectives at the same time. Instead of looking at a single view of an object, cubism brings all the angles and facets into play at once. When I’m working on a cubist-inspired piece, I think about how I can represent the fullness of an object or figure—not just what it looks like from one angle, but how it feels to experience it from all sides.

This can create a sense of movement, even in a still image. It feels alive because it’s not static—it’s constantly shifting, revealing different parts of itself as you look at it. In some of my pieces, you might see a fragmented face, where the eyes, nose, and mouth are all there, but they’re scattered, almost like shards of glass. You’re not meant to look at the face in a traditional sense, but rather experience it as something dynamic, something that can’t be pinned down to just one view.

Cubism and My Bipolar Experience

Being bipolar has had a huge impact on how I approach art, and cubism feels like a natural fit for that experience. My moods and thoughts can shift rapidly, and sometimes it feels like I’m seeing the world from multiple angles all at once. When I’m in a manic state, everything feels heightened—colors are brighter, shapes are sharper, and the world seems to pulse with energy. During those times, I can see the complexity of things more clearly, and cubism gives me a way to capture that in my art.

On the other hand, when I’m feeling low, the fragmented nature of cubism reflects that feeling of being scattered or disconnected. It’s like I’m piecing myself back together, bit by bit. The broken shapes and the way they don’t quite fit together perfectly mirrors how it feels to navigate those ups and downs. There’s something cathartic about taking the chaos in my mind and turning it into something visual, something that makes sense on the canvas, even if it doesn’t in my head.

Finding Balance in the Chaos

Cubism is often described as chaotic, and there’s definitely an element of that in my work. But what I find so satisfying about it is the balance that comes from the chaos. When you break something down into geometric shapes or fractured forms, there’s a tension between the disorder of the broken pieces and the harmony of how they come together. It’s almost like a puzzle, where the pieces don’t quite fit, but together they create something whole.

In my art, I play with this tension all the time. I might take a simple form, like a still life, and explode it into dozens of jagged shapes. But as I work, I try to find a way to bring those pieces back into balance, to make the whole greater than the sum of its parts. That’s one of the things I love most about cubism—it’s not about making things neat and tidy, but rather finding beauty in the fractured, in the imperfect.

Cubism in Color and Form

Another thing I love about cubism is how it opens up the use of color and form. When I break an object down into pieces, I’m not just thinking about the shape—it’s also about how the colors can shift and change within those fragments. Maybe a single object contains multiple colors, or the light hits it in a way that changes as you look at it from different angles.

In my work, this means I get to play with color in ways that feel completely free. I’m not tied to making things look "real" in the traditional sense. A single object can be red, blue, and yellow all at once, with each fragment of the shape catching the light differently. It’s a way of bringing more energy and emotion into the piece, using color to heighten the sense of movement and fragmentation that cubism is known for.

Why Cubism Still Feels Fresh

Cubism has been around for over a century, but it still feels incredibly relevant to me. It’s a reminder that there’s always more than one way to see the world, and that the reality we experience is often much more complex than we realize. It challenges the idea that things have to be represented as they are, and instead suggests that there’s power in breaking things down and putting them back together in new ways.

For me, cubism is more than just a style—it’s a way of thinking about the world. It encourages me to look deeper, to explore the hidden angles and perspectives that aren’t immediately obvious. It’s about letting go of the need for everything to make sense and instead embracing the fragments, the chaos, and the unexpected connections that come from seeing things differently.

In my art, cubism allows me to take something ordinary and turn it into something extraordinary. It’s a way of capturing the complexity of life, of emotion, and of experience in a way that feels true to how I see the world—fragmented, chaotic, but ultimately full of meaning.